The future of Quantum computing — the tech, companies, and roadmaps that map out a coherent quantum future

Analyzing the future of the Quantum computing industry.

Get 3DTested's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Looking ahead is rarely a good idea: the act of observation itself tends to collapse probabilities into smaller and smaller feasible options. But the future of an estimated $200 billion market by 2040 must nevertheless be looked at with intense scrutiny – plans and funding on groundbreaking yet specialized technology, such as quantum computing, demands that we do.

This isn’t a technical article – we won’t be taking any deep dives into many of the technologies mentioned, only briefly describing them. But this should serve as a good starting point for looking at the overall quantum technological landscape and its possible developments. We’ll be looking at some (but not all) of the current quantum computing approaches that have had the most promising and consistent developments – their futures inked into corporate roadmaps.

What this roadmap covers

Our approach is structured according to technology “families” among companies with deliverable products or services – think the superconducting qubits we’ve come to associate with IBM, Google, and Rigetti; trapped-ions (which have seen the most solid bets from IonQ and Quantinuum); quantum annealing and its particular track-record in optimization problems (D-Wave); neutral atom tech (Atom Computing, QuEra); and photonics (Xanadu, PsiQuantum).

Then, we cover research that has yet to bear fruit by looking at Intel’s work with silicon spin qubits, and Microsoft’s particularly embryonic topological qubits.

For this article, we’ll only look at superconducting qubits (as interpreted by IBM and Google) and trapped-ion qubits (as designed by IonQ and Quantinuum). Quantum is better taken in slices.

One thing to keep in mind throughout is that, like operating frequencies in processors, which aren’t a direct measure of performance, qubit quantity isn’t the be-all-end-all of quantum computing. The quality of qubits matters more than their quantity, even if quantity does improve quality up to a point.

Superconducting Qubits

Superconducting qubits, as the proximity to “superconductor” implies, take advantage of certain material’s ability to conduct electrical currents with no resistance. Qubits can be built out of these materials through what is called a Josephson junction – essentially, two superconducting layers separated by an insulating, 1-2 nanometer barrier. This junction then induces the emergence of discrete energy levels, which can be used to represent differentiated states (information). Computing is simply what is done to those states, and measuring their outcomes.

Superconducting qubits have the benefit of being compatible(ish) with contemporary 300mm semiconductor wafer fabrication technologies, which significantly improves perspectives on scaling, even if it means that inter-qubit connectivity is an obstacle (think CPU bus designs, and related technologies). However, the required near absolute zero operating temperatures and the degree of hardware cost and maintenance complexity means that superconducting quantum systems tend to be offered to customers via cloud platforms moreso than direct hardware sales.

IBM quantum roadmap

IBM splits its roadmap in two – a development roadmap, focused on the release of production hardware, software, and services available to customers; and an innovation roadmap, tracking the required scientific breakthroughs and internal proofs of concept that allow development to execute. IBM’s services started with cloud-based access to a 5-qubit system around May 2016, with cloud availability of its 20-qubit System One starting from 2019.

IBM’s latest executed hardware revision – Heron – is a quantum processor that offers a choice of 133 or 156 fixed-frequency qubits executed across 7.5K gates, and is part of the company’s current System Two architecture.

Nighthawk, IBM's 2025 execution-target (of which performance metrics are still absent), sees a step-back in qubit density, down to 120 qubits, and gate density, down to 5K gates, with a focus on systemic scaling. There's an increase in inter-qubit connections through L-coupling to improve performance and coherence. This architecture is to be expanded through 2028.

2026 sees a return to 7.5K gates while also allowing multi-chip scaling of up to three Nighthawk chips working in tandem (120 qubits *3).

By 2027, IBM expects to scale Nighthawk towards 10K gates feeding the same 120 qubits (a concession for increased coherence and accuracy) with up to 9 interlinked Nighthawk chips, bringing the total number of qubits up to 1080 (120*9). By 2028, Nighthawk is expected to scale up to 15K gates.

2029, however, is where IBM plans to have error mitigation matured enough so as to achieve their promise of a fault-tolerant quantum processor in the form of Starling. The architecture differences are expected to be significant, with a 100 million gate design powering 200 logical qubits.

By 2033, IBM expects its architecture to scale tenfold, with Blue Jay chips delivering 2000 logical qubits across 1B gates. The roadmap reads this moment as the keystone for unlocking “the full power of quantum computing” – powerful enough systems to demonstrate quantum advantage on several key addressable classes of problems.

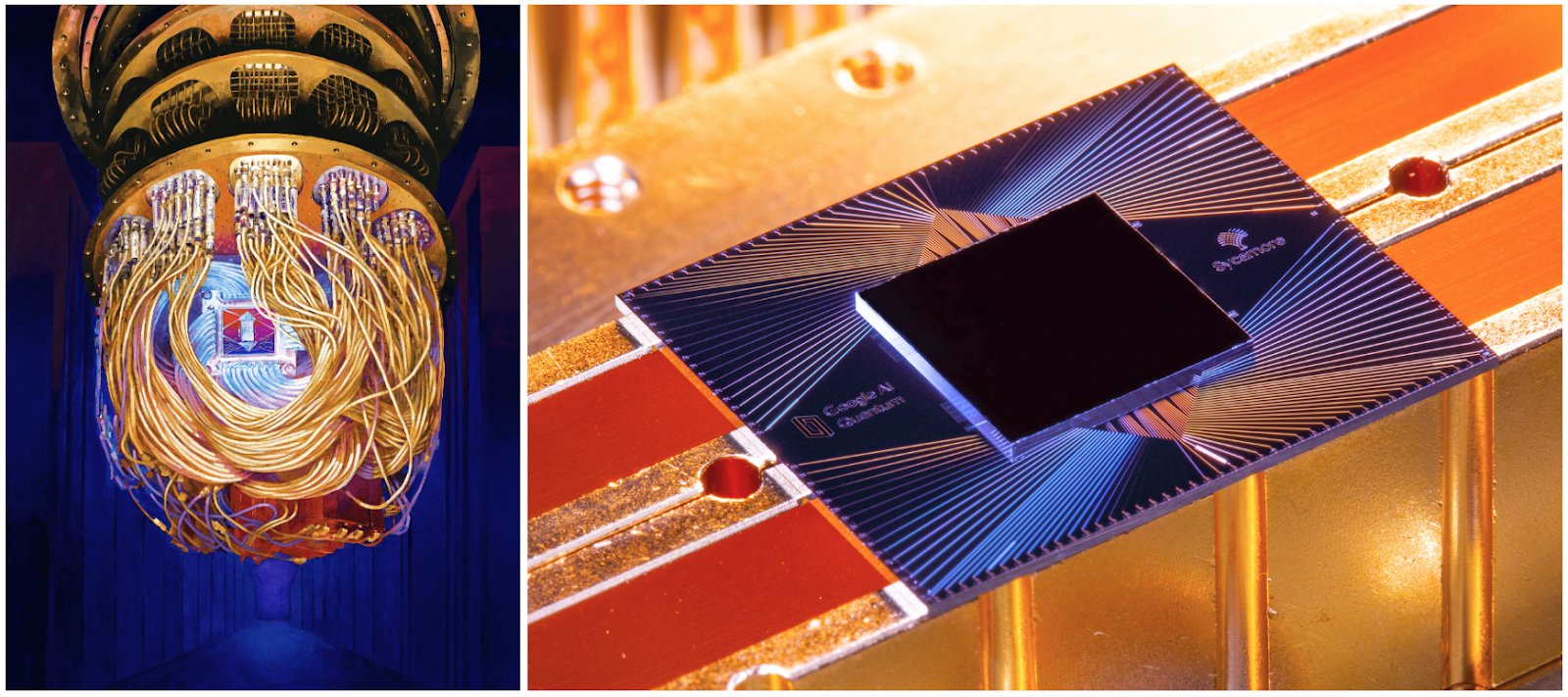

Google Quantum Roadmap

Google is now marketing its quantum computing efforts under the “Quantum AI” tagline, and its public roadmap is much less coherent than IBM’s – there are no public commitments to specific performance metrics or qubit counts, nor a describable timeline for the innovations the company is planning on executing on the road to fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The company does seem to be eyeing up quantum computing through an AI-focused lens: as they put it, “quantum computation will be indispensable for collecting training data that’s inaccessible to classical machines, training and optimizing certain learning architectures, and modeling systems where quantum effects are important.” Google definitely has a plan for the future of quantum – but the relative opacity opens up questions.

Google’s current hardware revision for quantum processors is Willow – a 105-qubit superconducting-qubit chip that the company claimed showcases quantum advantage (in this case, being able to perform calculations that are deemed impossible for classical computers to solve within even the lifetime of our observable universe). These claims are always met with backlash – more than once have we seen algorithmic developments in the classical computing space that unlock computations previously thought to only be achievable in the quantum realm.

Much like IBM, Google understands that qubit quality, coherence and interconnectivity are as important (if not more important) than raw qubit counts; while Willow was introduced in 2024, the company’s latest announcement in the area pertains not to a hardware revision but to improved error-correction algorithms, with their “Quantum Echoes” allowing for verifiable, cross-benchmarkable, repeatable quantum computing results.

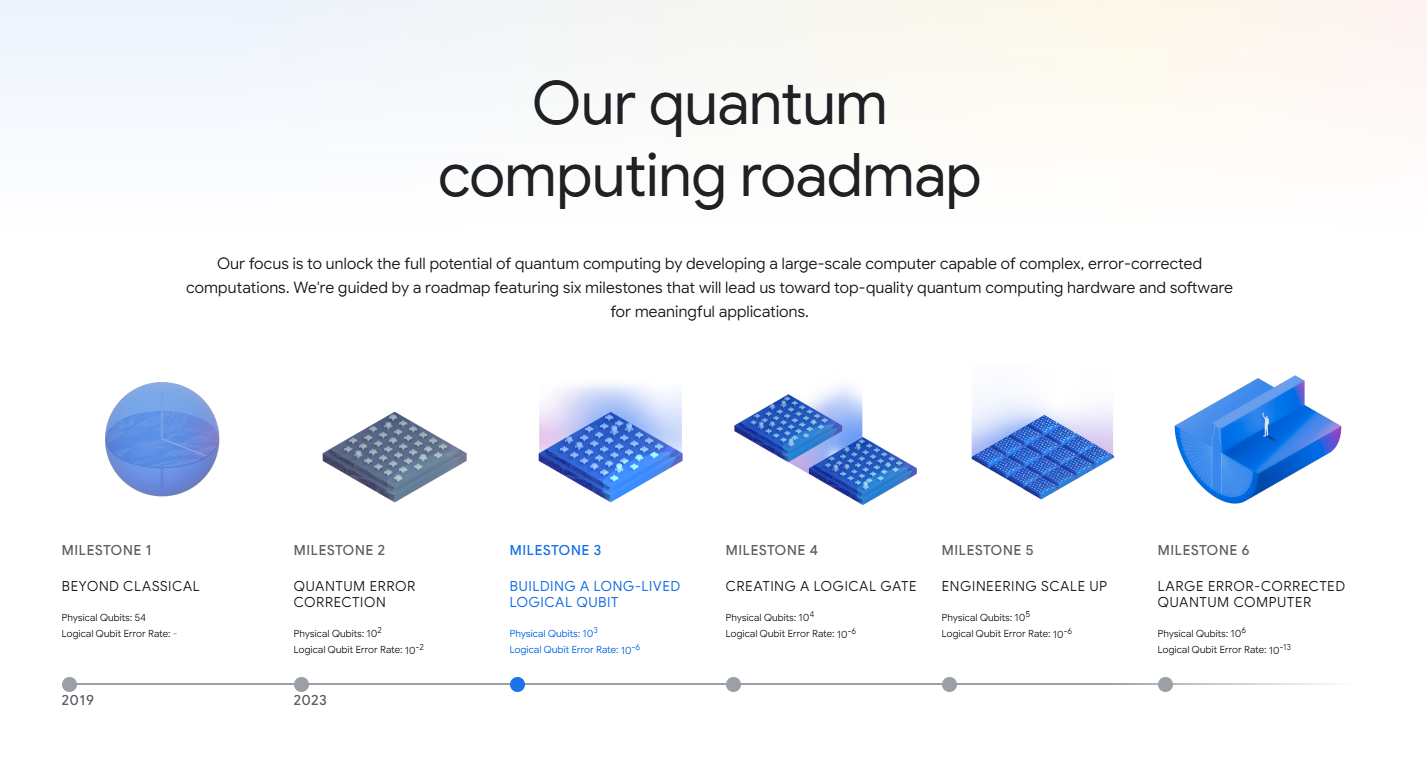

Google’s roadmap stands at Milestone 2 (achieved in 2023) out of 6, and it directly relates to their October 22, 2025 announcement on Quantum Echoes. This development bridges the gap to Milestone 3 – building a long-lived logical qubit, which the company defines as “capable of performing one million computational steps with less than one error”.

Milestone 4 relates to pairing these long-lived logical qubits in effective, logically-addressable quantum gates, while Milestone 5 looks at pairing multiples of these gates. The aim for Milestone 5 is to achieve up to 100 logical qubits tiled together for high-fidelity quantum operations, with an expected requirement of 10^5 (100,000) physical qubits to achieve it.

The end of Google’s current AI roadmap, Milestone 6, aims to achieve a “large error-corrected quantum computer” – one that operates on 1 million connected and controllable physical qubits. But again, there is no timeline.

There are inferences to be made between IBM’s public commitment, Google’s overall lack of clarity, and the perceivable architectural differences between both approaches. It's interesting to note that Google expects to uncover “10+ error-corrected quantum computing applications” through Milestone 6.

Trapped Ions

Trapped ion quantum computing is a wholly different beast from superconducting qubits – rather than Josephson Junctions, qubits are constructed of individual atoms (typically ytterbium or barium). These atoms are suspended in a vacuum and held stable in precisely-controlled electromagnetic traps at room temperature, with gate operations being typically performed through laser pulses.

These characteristics mean that trapped ion qubits are less susceptible to environmental noise than most other qubit designs, showcasing coherence times in the seconds-to-minutes range. Unlike superconducting qubits’ interconnectivity issues, trapped ions can be designed to have all-to-all connectivity.

Hardware complexity (especially when it comes to laser pulsing) does remain a snag in scaling, and the speed of quantum calculations is limited by laser-based technology. Their useful states last longer than superconducting qubits might, but they are usually slower to retrieve useful work from.

IonQ acquired Oxford Ionics in June 2025, prompting a new way of looking at trapped ions – one that, like superconducting qubits, can take advantage of semiconductor manufacturing to tackle specific scaling issues.

IonQ

IonQ started offering quantum computing services in late 2017 by selling the first commercial trapped-ion quantum computer – a direct-sales model which was then complemented with cloud access to compute starting from 2019 (first through Amazon Bracket, then Azure Quantum, and Google Cloud Marketplace in 2021).

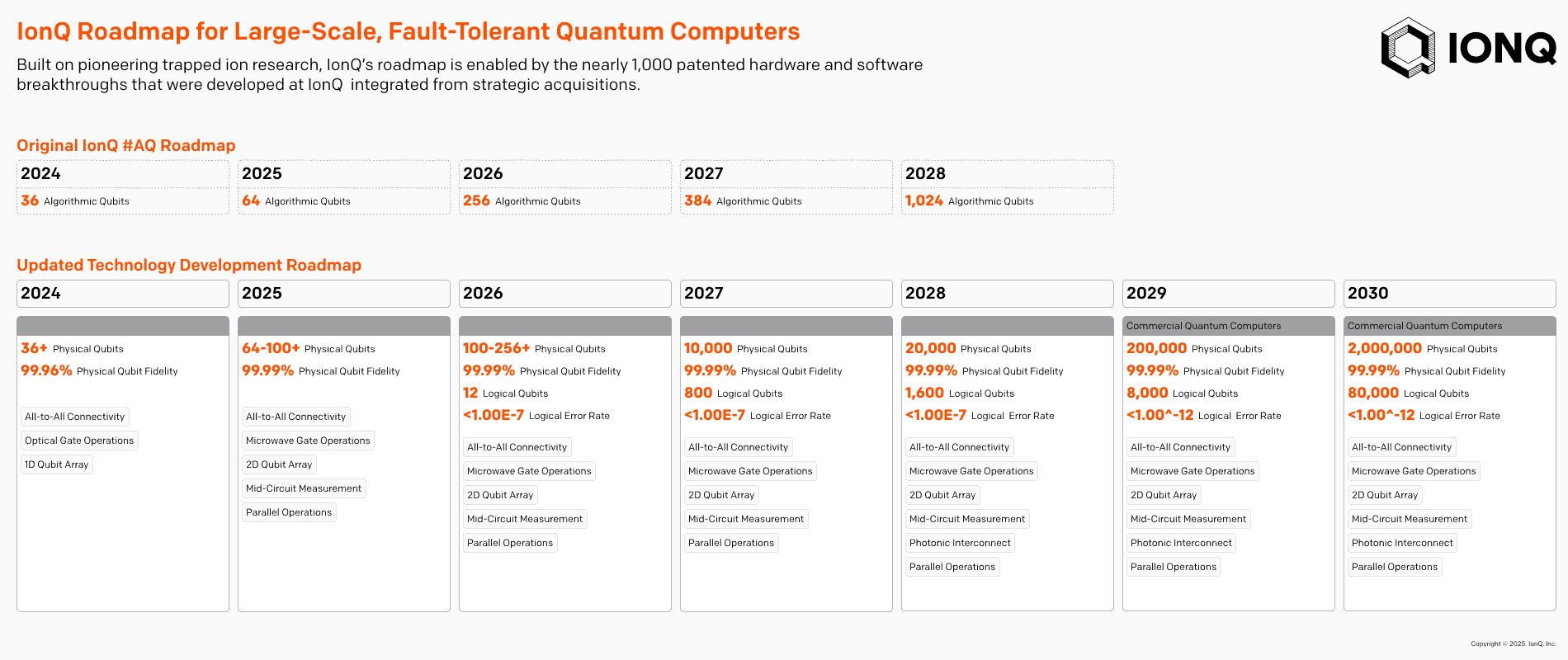

There’s perhaps no point in looking at IonQ’s roadmap before June 2025, when IonQ took a specific strategic turn with its announced acquisition of Oxford Ionics, the results of which are already part of the company’s roadmap. 2025 saw IonQ delivering on their Tempo architecture three months ahead of schedule while pushing the number of physical qubits up to the revised roadmap’s promised 100, while also demonstrating the base working architecture that will allow their 2026 product to more than double that, up to 256 qubits.

This evolution is made possible by IonQ’s move from ytterbium atoms to barium atoms, paired with IP integration from Oxford Ionics (which replaces the laser array with chip-carried microwave control) alongside Lightsync’s interconnect and quantum memory architecture. Through the microwave control replacing the laser control system, a lot of the difficult-to-scale parts in the overall trapped ion architecture become compatible with wafer manufacturing techniques, which helps explain the much increased confidence in IonQ’s new roadmap.

The company previously expected to achieve 384 algorithmic qubits by 2027 (a performance measured used only by itself), the new architecture has moved that goalpost to actually physical and logical qubits, promising systems with as many as 800 logical qubits across 10,000 physical qubits.

By 2028, the company aims to double that to 1,600 logical qubits across 20,000 physical qubits with the full integration of Lightsync’s IP in its photonic interconnect. By 2029, IonQ plans to go further with a design featuring 8,000 logical qubits across 200,000 physical qubits. A note on the slide adds that the company believes this is the era for actual viable, performant commercial quantum computers.

By 2030, the company expects to achieve what is claimed to be the highest number of available qubits on a product (whatever form it might eventually take), with a tenfold increase to 80,000 logical qubits across 2 million physical qubits. However, what that might look like in terms of actual performance remains to be seen.

Quantinuum

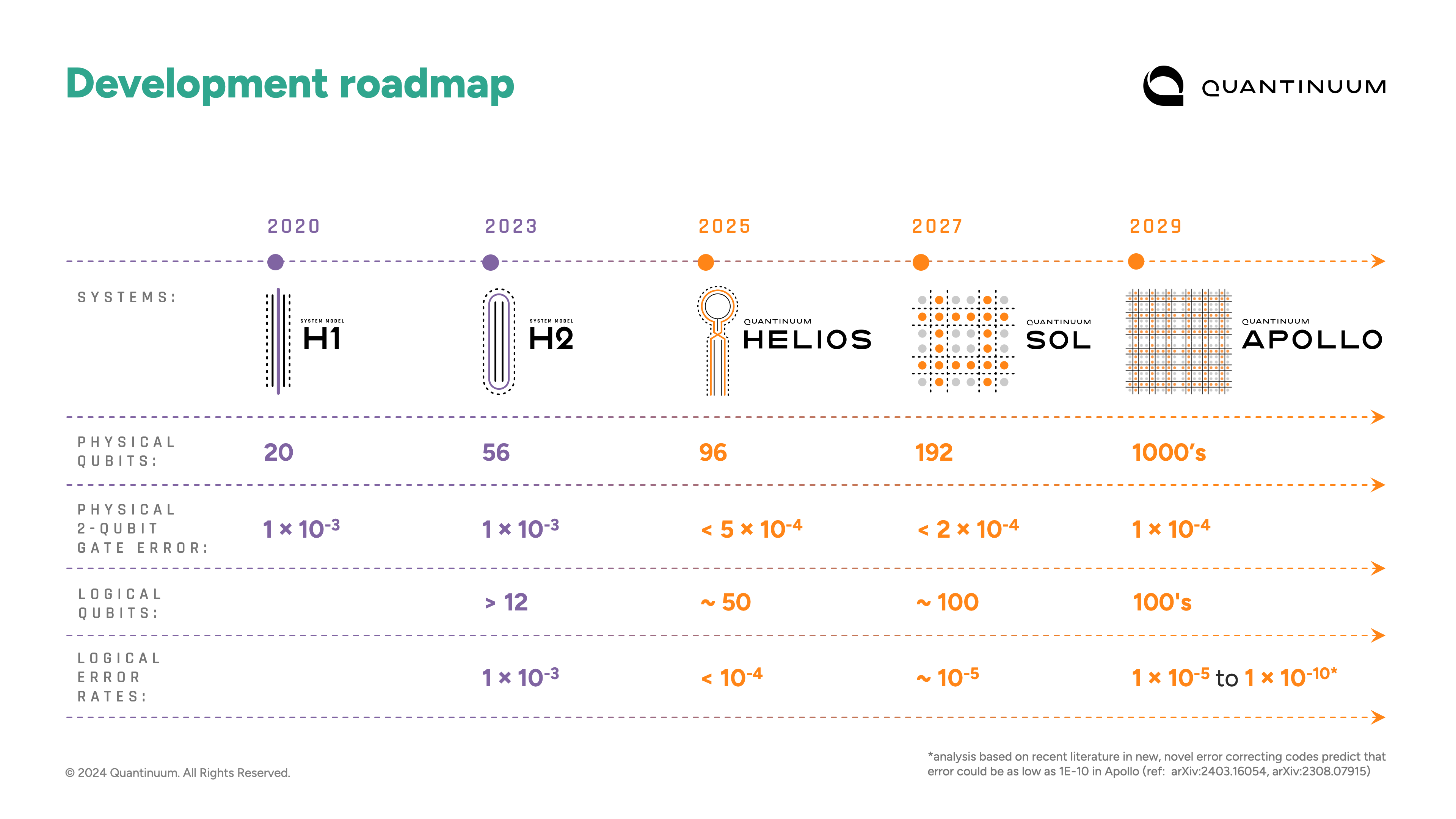

in Singapore by 2026 through a collaboration with the National Quantum Computing Hub (NQHC), with a focus on solving problems in finance, pharmaceuticals, and materials science. Quantinuum was founded in November 2021 as a result of a merger between Honeywell Quantum Solutions and Cambridge Quantum Computing. Before that, Honeywell offered commercial quantum computers starting with the H1 in October 2020 (offering 10 interconnected qubits), and their solutions, before evolving into its current model, available through direct cloud or delivered through Microsoft’s Azure Quantum, with their 2025 Helios model now being made available for on-premises installation.

Quantinuum’s Helios is the company’s execution on its 2025 roadmap, offering Barium-atom-based qubits at counts of 98 physical and 48 logical – a switch from the Ytterbium atoms they too previously used (and a technological convergence with IonQ, up to a point).

A physical installation is expected to occur by 2026 in Singapore through a collaboration with the National Quantum Computing Hub (NQHC), with a focus on solving finance, pharmaceutical, and material science problems.

By 2027, Quantinuum is looking to introduce its Sol architecture, which will integrate a 2D-grid-based qubit design to double qubit counts (192 physical and, one would guess, 96 logical), besides a focus on improving error correction capabilities.

It seems that Sol is more of a validation vehicle for Quantinuum’s architecture choice in the lead-up to 2029’s Apollo, which is the point at which he company’s roadmap also becomes blurry – we’re now met with projections that Apollo is expected to hit thousands of physical qubits with a correspondingly uncertain number of hundreds of logical qubits. But Apollo doesn’t yet seemingly meet the requirements to be Quantinuum’s own “large error-corrected quantum computer”; it seems more of a demonstration vehicle for a fully fault-tolerant quantum computer.

Scale is expected to come from its successor, Lumos, which hasn’t even been added to the available roadmaps yet, but has been mentioned for a 2033 release via its selection by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) for stage B of the agency’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative (QBI).

The future of Quantum is being paved

This is but a partial view of the quantum computing landscape – we covered two technology areas and only two companies in each. Google proved to have the most opaque roadmap, but it’s also the biggest company on the list by market cap alone (a reduced advantage in a field where the bottleneck isn’t money, but specialists and IP). But this view still offers a good sense of what's to come for Quantum machines.

For one, all four companies we looked at appear to be mapping out large-scale, error-corrected quantum computers around and beyond 2030. That’s when the utility explosion is expected to happen. On the road there, the trapped-ion side seems to be leaving laser-based interactions and opting for 2D placement of atoms to increase scaling and qubit density with such confidence that IonQ claims to have the most scaling-friendly architecture available.

The superconducting side of the coin appears to be focused on error-correction and architecture fine-tuning, and is conservative in raw qubit count scaling when compared with the trapped-ion roadmaps.

Perhaps one way of looking at commercial and technological viability for the differing quantum architectures is by looking at those that made it into stage B of DARPA’s QBI, which include IBM, Quantinuum, and IonQ – out of the ones we looked at in this article, Google (and its very tentative roadmap) is the only absent player.