China’s AI build-out forces a rapid shift to liquid cooling — massive clusters put pressure on domestic suppliers to shift cooling methods

‘Exaflop-scale’ clusters pressure domestic suppliers to localize a supply chain for liquid cooling.

Get 3DTested's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

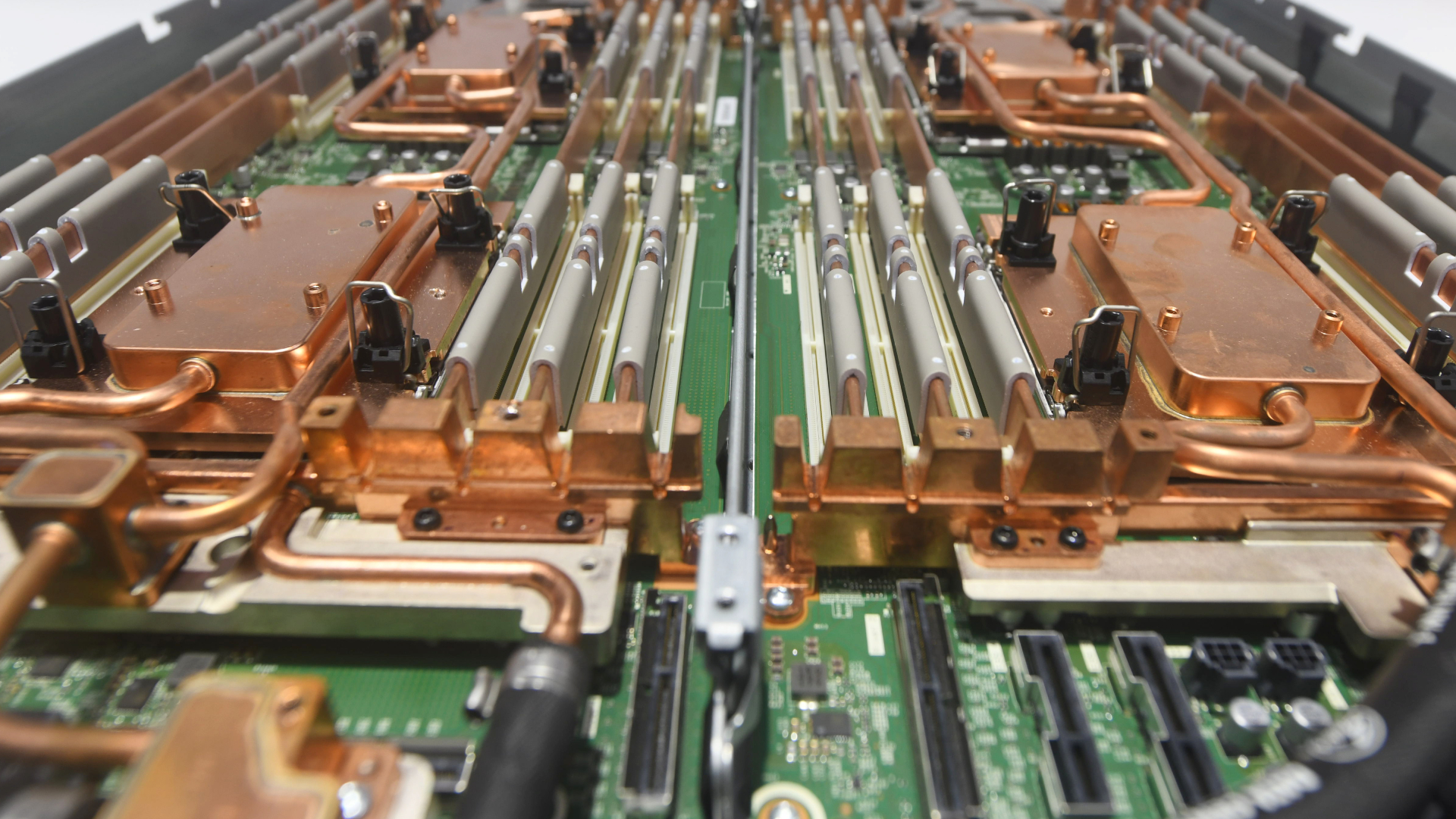

Walk into any modern AI data center, and you’ll immediately be hit in the face by heat. Even before you’ve set your eyes on the racks, you feel the output of rows upon rows of servers pushing air through increasingly dense racks that were never designed for processors drawing the sheer power needed to run huge AI models. Multiply that across dense training clusters, and the thermal envelope becomes one of today’s greatest engineering constraints.

Now, according to reporting by the South China Morning Post, China is accelerating investments in liquid cooling technology. Dozens of Chinese companies — including Envicool, whose shares have more than tripled over the past year — have announced plans to expand into liquid-cooling systems to prevent AI racks from overheating. With thermal envelopes riding, this isn't a problem unique to Chinese data centers, either.

Since 2022, Beijing has pushed its “Eastern Data, Western Computing” strategy, which shifts data processing toward western provinces with access to renewable energy. According to China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the country has already built 42 “10,000-card” intelligent computing clusters, with total capacity exceeding 1,590 exaflops. Those clusters aren’t populated with low-power CPUs but built around high-end AI accelerators that concentrate enormous heat loads into increasingly compact footprints.

Air cooling won’t cut it

As an example, Nvidia’s B200 operates at more than 1,000 watts per processor, and its GB200 NVL72 rack-scale platform, which integrates 72 Blackwell GPUs and 36 Grace CPUs, ships in a liquid-cooled configuration as standard and out of necessity.

As chip thermal design power continues to climb, air cooling faces two limits. First, the volumetric heat capacity of air constrains how much thermal energy can be removed per unit time without driving airflow and energy use to impractical levels. Secondly, high airflow requirements complicate rack density and overall facility design. At multi-kilowatt per rack densities, these air-cooled systems become increasingly inefficient.

Liquid, by contrast, offers orders of magnitude higher heat capacity and thermal conductivity. Direct-to-chip cold plates circulate coolant through sealed loops attached to processors, removing heat at the source. More aggressive approaches, including immersion and spray cooling, place components in direct contact with dielectric fluids. This has created an all-new bill of materials consisting of cold plates, manifolds, leak-detection systems, and cooling distribution units, among other components.

Global suppliers like Vertiv are prominent in this stack, but Chinese firms are racing to localize capabilities. Envicool, whose customers include Nvidia, Alibaba, and Tencent, has become one of the most obvious domestic players, with Goldman Sachs and UBS both raising price targets on its stock, citing demand tied to AI and energy efficiency.

Growing model sizes

China’s tilt towards liquid cooling isn’t driven solely by chip thermals, though. Its national energy and carbon reduction policies impose explicit power usage effectiveness targets on data centers. Power Usage Effeciveness (PUE) is the ratio of total facility energy to IT equipment energy, and becomes harder to optimize as cooling overhead rises. Liquid systems, by reducing fan loads and enabling higher coolant temperatures, can materially improve overall efficiency.

Despite offering renewable energy resources, the country’s western provinces lack the legacy data center infrastructure found in the coastal regions. Building greenfield AI campuses allows operators to design around liquid cooling from the get-go, rather than retrofitting air-cooled facilities. That design freedom will reduce friction in adopting direct-to-chip or immersion cooling architectures at the scale China needs.

Meanwhile, Chinese hyperscalers downstream are piling on the demand pressure. Their model sizes are growing, and their training runs stretch across thousands of accelerators, thereby making thermal reliability a serious performance variable because any temperature gradients across racks can affect clock speeds and error rates.

A new battleground

The narrative around AI hardware has centered on GPUs and memory for years, and now cooling is joining that list. Vendors that can deliver integrated rack-scale solutions that combine accelerators, networking, and liquid thermal management will gain an edge in both deployment speed and operational efficiency.

Vertiv, an Ohio-based data center infrastructure provider, recently reported net sales of about $13.5 billion. It’s also a partner of Nvidia, placing it directly in the path of Blackwell deployments. Chinese counterparts are understood to be pursuing similar alignments within domestic supply chains, particularly as export controls will continue to complicate access to certain U.S. Components.

Ultimately, the question is not whether liquid cooling will become the default for AI infrastructure, but how quickly. With Blackwell-class GPUs exceeding 1,000 watts and rack platforms consolidating dozens of these components, air cooling appears increasingly confined to lower-density inference workloads. Even there, analysts expect liquid adoption to rise, albeit at a slower pace than in training clusters.

Returning to China — “10,000-card” clusters pushing 1,590 exaflops will mean that even marginal gains in cooling efficiency via liquid cooling could translate into significant energy savings and better overall stability. China just needs to establish an entire supply chain to achieve it.