55 years ago, the first computer search warrant was issued — in February 1971, a Santa Clara judge authorized police to seize punch cards and a 'computer memory bank'

Authorities were looking for a trade secret. Stories involving digital forensics remain very topical over half a century later.

Get 3DTested's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

55 years ago, in a courthouse serving the San Jose-Milpitas district of Santa Clara County, a judge for the first time signed a search warrant that treated a computer system as something that could be searched, and its content seized. Dated February 19, 1971, the order authorized Oakland Police to enter offices in Palo Alto and homes in Menlo Park to look not just for papers but also for data stored on machines.

The case involved University Computing Company and a program described in court documents as a remote-plotting system (a trade secret) valued at $15,000, or around $120,000 today. In his affidavit, Sgt. Terence Green requested authority to seize “computer memory bank or other data storage devices,” along with “computer printout sheets,” language that shows how investigators might have been struggling to grapple with the concept of intangible forms of property at a time when most computing infrastructure would fill entire rooms.

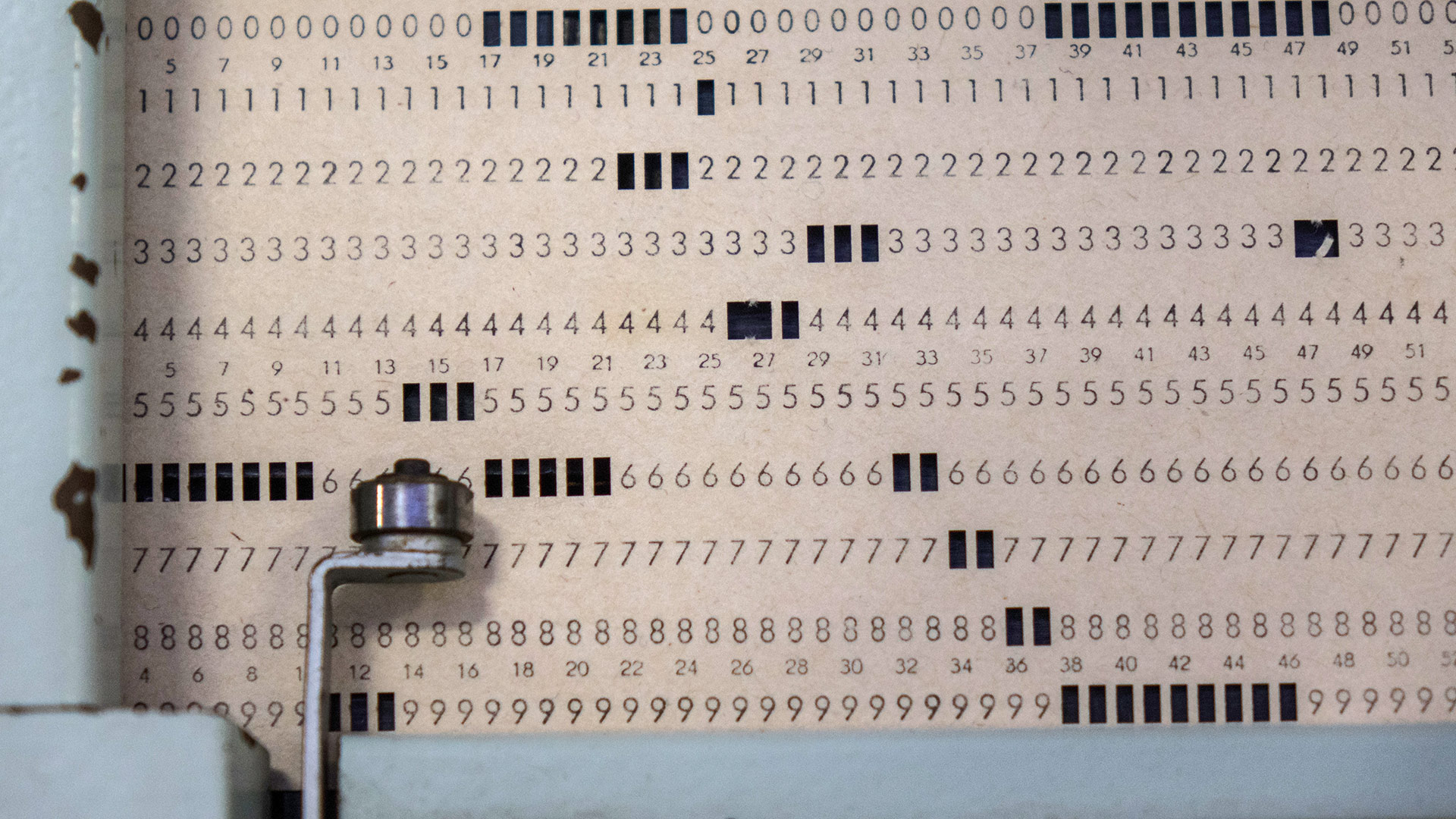

Central to the dispute were punch cards, the dominant medium for program storage and job submission at the time. The affidavit describes “a deck of key punch cards” tied to the remote plotting program. Each card represented a line of code or data, meaning a full program could be made up of hundreds or thousands of cards that had to be meticulously kept in order.

By the late 1960s, IBM’s 80-column punched card format had effectively become the industry standard, meaning systems from multiple vendors were built around reading and writing this layout. This also meant that a stolen program could be as tangible as a misplaced deck of cards. At the same time, once those cards were written to storage, the program no longer existed solely on punch cards, which explains why investigators sought authority to seize both the physical cards and the “computer memory bank or other data storage devices” that might contain the same code in electronic form.

The warrant itself would later be reproduced in Jay Becker’s The Investigation of Computer Crime, published as part of the National Center on White-Collar Crime’s operational guide. A copy of an “actual state search warrant” appears in Appendix 5 of the report. Becker.

Early digital forensics

Becker’s manual offers a glimpse into how investigators in the early 1970s were already wrestling with now-routine problems in digital forensics. In the section titled “The Nature of Computerized Evidence,” he notes that evidence in a computer is “more ‘dense’ than in any other information system,” describing how what appears to be a single computer tape can contain as much information as “a shelf full of books.” Much of that information, he explains, is invisible without translating the machine-readable symbolism into print.

According to the reproduced documentation, investigators conducting the February 1971 search didn’t simply remove hardware, but generated printed directories of files stored on the system and produced magnetic tapes to preserve the contents. Becker emphasizes that in some cases it may be “desirable, if not necessary, to duplicate the controls” of each information-storing device, whether tape, disk, or card, so that subsequent changes cannot compromise the evidentiary record.

Get 3DTested's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Becker goes on to warn that search warrants in cases involving computers must be narrowly defined because the system may contain “an enormous amount of description for the investigator to cover each component of the computer system which he seeks to inspect or seize.” That concern about overbreadth and technical unfamiliarity would later be a foundational concept to jurisprudence concerning digital search and seizure.

More than half a century later, storage media and network architectures might have changed beyond recognition, but the underlying problem identified by Becker has not. Meanwhile, crime taking place in and evidenced by the digital domain often dominates the newswires.

Follow 3DTested on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.