Microsoft's Project Silica write-once storage could store terabytes of data for over 10,000 years — company explores two physical glass storage methods, so the glass-clad future of storage isn't coming anytime soon

Microsoft is working on two radically different mechanisms.

Get 3DTested's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Microsoft Research has been working on Project Silica — a glass-like write-once storage device that can store terabytes of data for 10,000 years — for well over five years now, without making any promises about its commercialization or disclosing detailed technical information. This week, the company finally detailed its mediums and end-to-end workflows in Nature, which is meant to confirm that the project is still under development, but without making any promises about commercialization.

The main concern around Project Silica is that Microsoft Research is now working in two different directions that rely on two fundamentally different physical mechanisms, which means that nothing is ready for prime time yet.

Two different writing methods

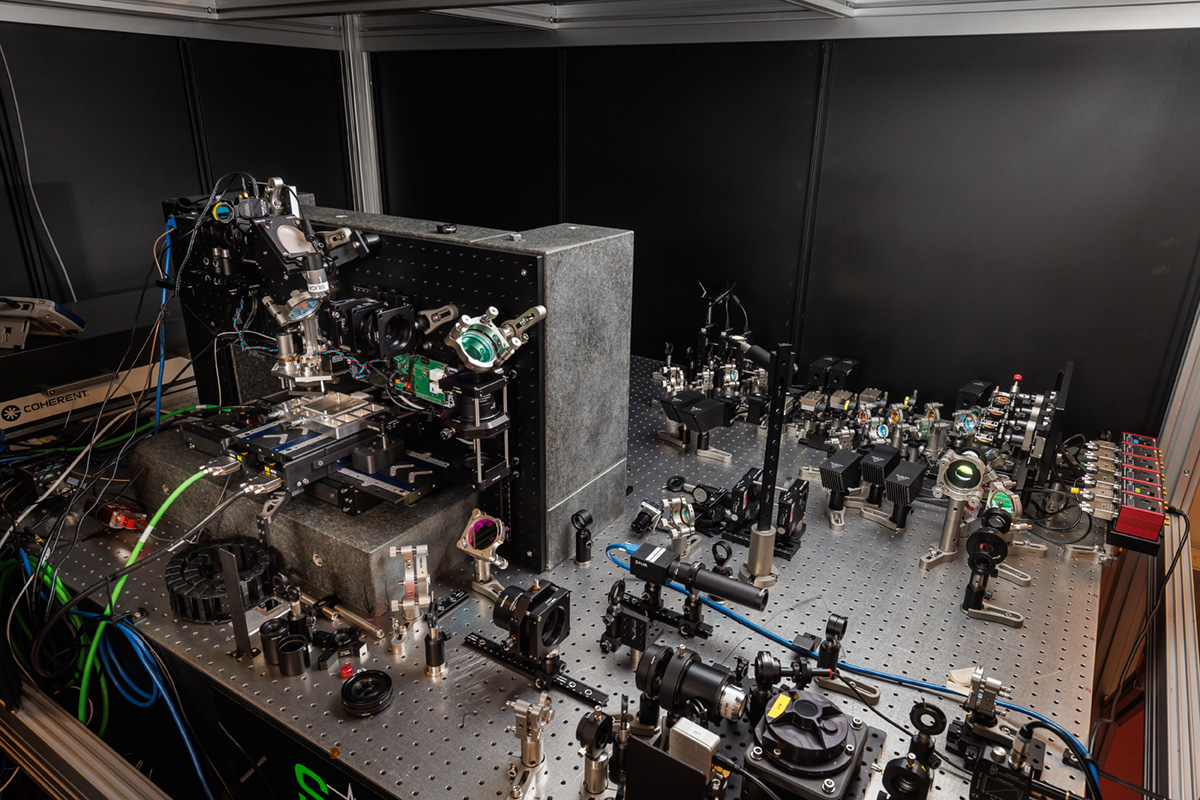

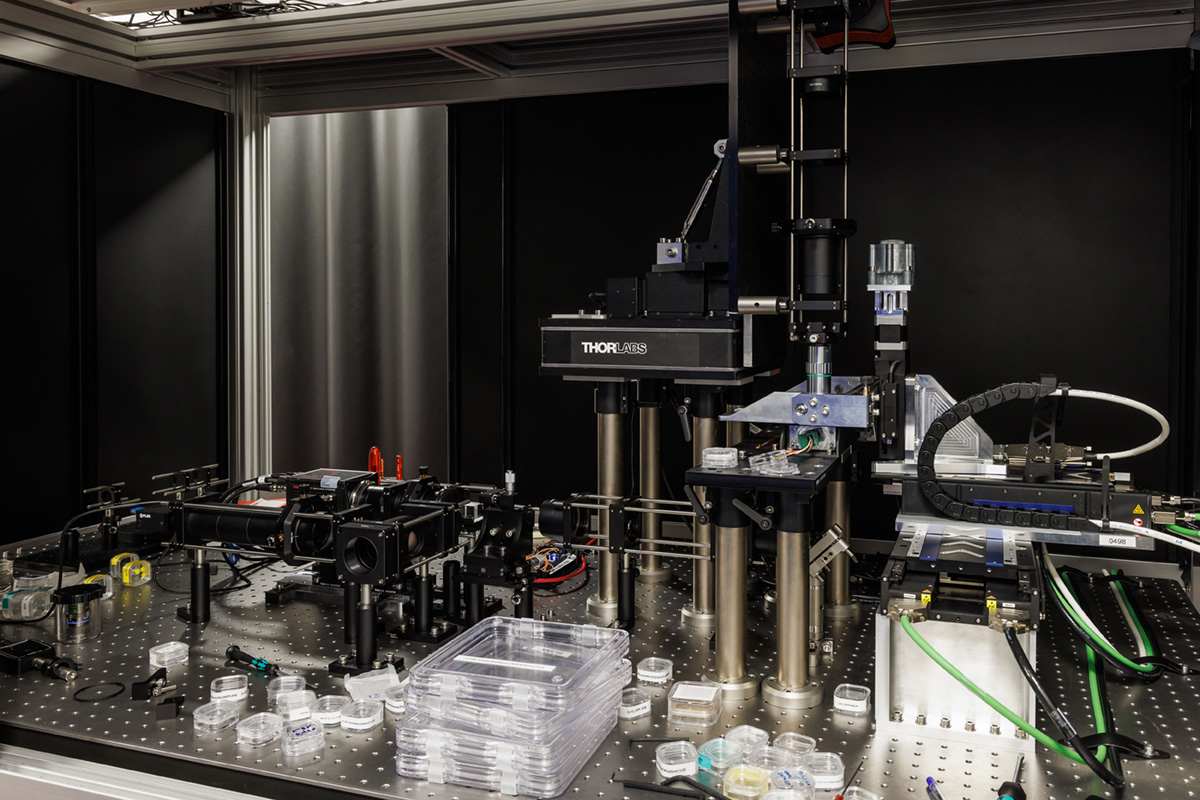

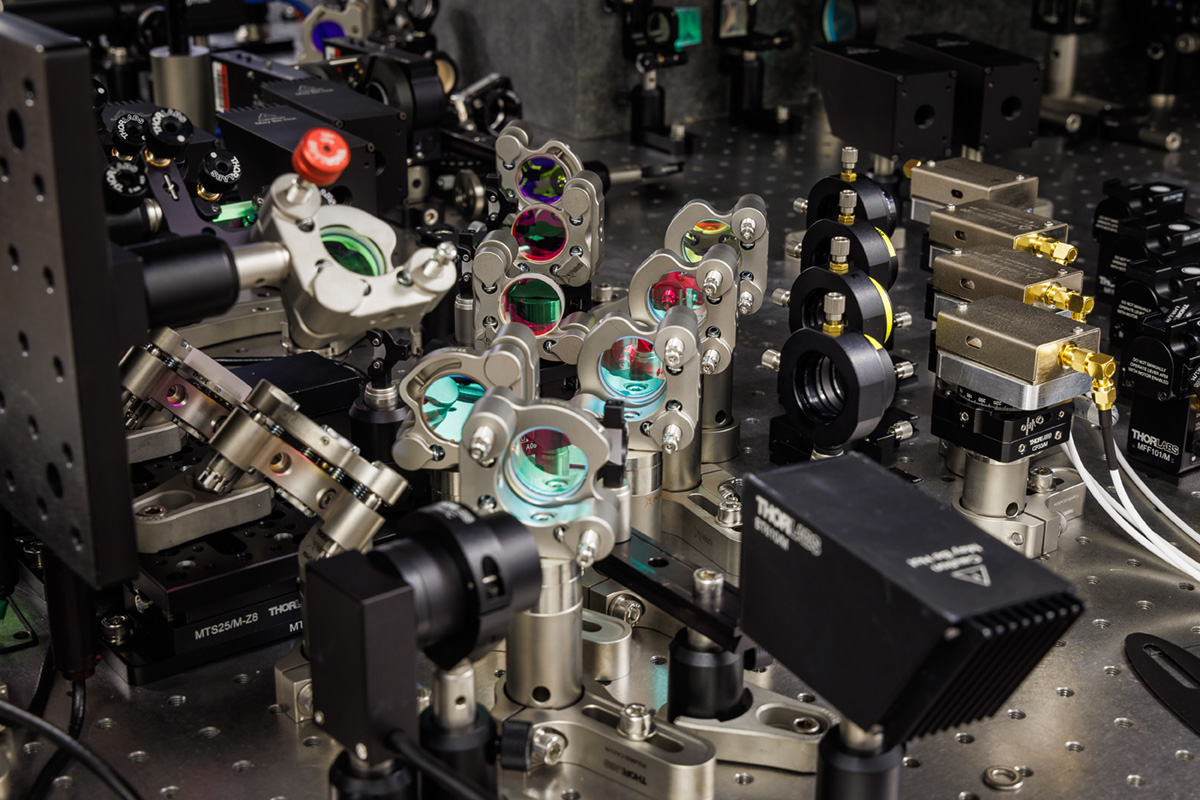

The first method leverages the original Project Silica write-once read-many (WORM) storage solution and relies on fused silica medium and femtosecond laser pulses to create microscopic data points — voxels — stacked across hundreds of layers. The revamped method relies on a pseudo-single-pulse approach in which each laser pulse is split into seed and data components: the seed pulse initiates a nanovoid, and the following pulse elongates it to produce the final birefringent voxel state. Eight polarization levels are encoded per voxel.

This method enables a voxel pitch of 0.500 µm × 0.485 µm, 6 µm layer spacing, and 301 layers. Thus, the medium reaches 1.59 Gbit/mm³, which translates to 4.84 TB usable capacity in a 120 mm × 120 mm × 2 mm glass platter after overhead. From a performance point of view, we are talking about 25.6 Mbit/s per beam and 10.1 nJ per bit energy efficiency.

The second method introduces phase voxels, a new storage primitive that modifies the refractive index of the glass to create phase shifts in transmitted light. A phase voxel contains four levels of amplitude modulation and requires only a single femtosecond pulse to modify its phase. More importantly, they can be formed reliably in borosilicate glass, the same material used in cookware and oven doors.

At a 0.5 µm × 0.7 µm pitch, 7 µm interlayer spacing, and 258 layers, density reaches 0.678 Gbit/mm³, which means 2.02 TB per platter with four modulation levels at a 0.92 quality factor. Throughput per beam is 18.4 Mbit/s, and energy efficiency is 8.85 nJ per bit. In addition, by splitting the beam into four independently modulated channels, researchers demonstrated 65.9 Mbit/s without inducing thermal damage, and they believe that 16 or more beams should be feasible.

Two different retrieval methods

As there are two different types of voxels, Silica uses two distinct optical retrieval methods, each corresponding to the physical nature of the stored voxel.

For birefringent voxels in fused silica, the system relies on polarization-resolved wide-field microscopy. The written nanostructures change light in a direction-dependent way (anisotropically), so to read the data, the system shines circularly polarized light through the glass and captures images in three different detection states, spaced 120° apart on the Poincaré sphere. Using these three views, the reader can reliably tell apart the eight azimuth orientation levels stored in each voxel. The system uses a 0.6 NA objective with spherical aberration correction to maintain good resolution while reading deep into the glass, and it captures one focal plane per layer.

For phase voxels in borosilicate glass, retrieval is performed using a custom Zernike phase-contrast microscope. These voxels store data as small changes in refractive index, which create phase shifts in transmitted light. To read them, the microscope uses a phase ring inside the objective to convert the tiny phase shifts into visible brightness differences.

Unlike the birefringent approach, this method has weaker optical sectioning, so signals from neighboring layers can interfere more easily, which needs mitigation. To mitigate, the reader captures two images per layer: one at the position of strongest contrast and another slightly deeper in focus, where the voxel signal reverses (contrast inversion). Comparing these two images reduces axial cross-talk and improves the ability to distinguish between the four amplitude levels written per voxel.

Both retrieval methods rely on wide-field imaging with a CMOS camera (Hamamatsu ORCA Flash4 v3.0, 2048 × 2048 pixels) and automated track positioning. Once the images are captured, the system recovers the data in four main steps. First, it cleans up and aligns the images. Next, a convolutional neural network analyzes each voxel and estimates which symbol was written. Those symbols are then converted back into bits, and finally, an LDPC error-correction stage reconstructs the original user data.

Rather than looking only at raw bit error rate (BER) or symbol error rate (SER), the researchers use something they call a 'quality factor,' which measures how much redundancy is needed to reliably recover all the data. So, instead of just asking 'how many errors are there?', they ask 'how much correction is required to guarantee full recovery?' This is a normal approach for research as it represents a more practical way to determine archival reliability. However, for a commercial storage system, a solid correction mechanism is needed.

Validated longevity testing

To validate reliability, the Microsoft Research team did not stop at lab-scale demonstrations, but subjected Silica to repeated write-and-read cycles across multiple glass samples over several months.

The researchers wrote the same dataset onto three different glass platters and then read the data back a total of 37 times, each time using LDPC error correction to fully reconstruct it. The results were remarkably consistent: the variation in the quality factor was extremely small — just 0.00230 between the middle 50% of reads — which translates to about a 0.25% difference in the median density, a good result for a technology that is in a research phase. That said, the performance was stable and repeatable, not a one-off lucky run.

For endurance, the researchers conducted accelerated aging experiments by annealing phase-voxel samples at 440°C, 460°C, 480°C, and 500°C in a controlled furnace. While the samples were heated, they measured how the diffraction signal gradually weakened over time. From this decay, they calculated an activation energy of 3.28 eV, which is relatively high and which means the refractive-index modifications are thermally stable. Arrhenius modeling projects media lifetime exceeding 10,000 years at room temperature, which is consistent with the promised millennial-scale data retention.

Different directions, zero promises

The publication in Nature once again demonstrates that Microsoft Research can achieve formidable storage density using glass media and unprecedented reliability. Yet, it does not look like Microsoft is actually close to commercialization of the technology.

The main design decision for future Silica systems — whether to deploy birefringent or phase voxels — has not been made. Birefringent voxels deliver higher density and higher performance (while still being orders of magnitude slower than HDDs), but they require high-purity fused silica to form stable anisotropic nanostructures. Phase voxels, demonstrated in borosilicate glass, are more flexible in terms of materials and simplify the hardware stack, but at the cost of lower storage density and even lower performance. Both approaches operate at the full 10 MHz laser repetition rate, so neither is inherently limited in pulse-level throughput.

Good news, the roadmap for scaling is clear. Increasing the write objective numerical aperture from 0.6 to 0.85 could roughly halve write energy and reduce voxel volume by about 4X, assuming NA scaling. Higher-performance glass compositions with lower modification thresholds could improve voxel quality and efficiency, while commercially available 50 MHz femtosecond lasers combined with multi-beam multiplexing could raise performance by 20X in the best case scenario, which will bring the technology on par with hard drives in terms of performance. Read performance will mainly depend on camera speed and large field-of-view optics, and was not considered a major cost factor.

At the system scale, a cloud implementation would use robotic glass libraries to automate media handling, which, in conjunction with reliability and longevity, makes Silica a viable long-term archival storage technology. The main question is when is this technology might be ready.